Housing London’s Diverse and Growing Population

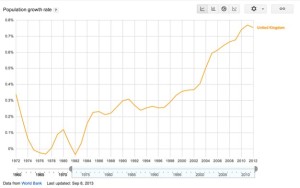

London’s population has been reported to have increased by more than 100,000 last year to a new postwar high, and at the current rate of increase will hit a total of nine million people by 2019, according to the latest data from the Office for National Statistics.

As a result the city needs a more extensive transport network for commuters, says London Mayor Boris Johnson, and 400,000 new homes over the next 10 years. Population up, prices up, rents up, supply very, very low – the equation does not work, it is only by the immediate increase in new housing in London can disaster be averted.

The popular suburbs are where the population is predicted to grow and there will be significant growth on the East side of London both North and South of the Thames. After past flirtations with locating offices out of town, the mood is now for commerce to cluster in the centre of the capital, though this will inevitably put extra strain on the transport system. So London will not just have more people — predicted eventually to reach 10 million by 2030 — it will have more people travelling longer distances to work.

Private car use in London is falling, while journeys by Tube and bus are soaring. Once-quiet public transport routes are crammed, with 3.7 million people using the Tube each day. The Docklands Light Railway carries 100 million passengers a year, up from 66 million in 2008, while the recently completed East London line is already feeling the strain — though its capacity is being boosted by 25 per cent.

THE most recent census of Britain, in 2011, found few places that were less populous than they had been in 2001. Most of the shrinking districts were in the post-industrial north of England. But an unexpected addition to the list was Kensington and Chelsea, London’s wealthiest borough, where the population shrank slightly. There, houses are kept empty by rich foreigners who buy them as investments or as occasional summer homes.

The Capital’s population – which stands at around 8.2m – last peaked at 8.9m in the 1930s, at which point around 60,000 homes were being built a year. However, London’s current residential construction pipeline equates to an average of just 28,500 new homes a year, suggesting an annual shortfall of 21,500.

An increase in homelessness, rough sleepers on the street, enormous waiting lists for social housing, young professionals unable to move out of their parents’ home and more bedrooms being squeezed into rented accommodation are all signs of housing crisis. The Royal Bank of Scotland and Halifax have reported a strong uptake in the Government’s Help to Buy scheme – having received a total of 2,384 applications potentially worth £365m in mortgages. This will hopefully unlock the lower end of housing market for first time buyers by providing security on 95pc loans.

It is the broader surge of foreign money into London housing, irks many. Simon Hughes, the Liberal Democrat MP, argues that foreigners are pricing British people out of owning homes. Ed Balls, the shadow chancellor, complains about “foreign investors buying multimillion-pound houses in London and not paying tax.” The government is considering introducing capital-gains tax on foreigners selling investment properties. Like owner-occupiers, but unlike Britons who own more than one home, they are currently exempt.

The London property market is complex and the charge that rich foreigners are denuding central London of people, is unfair. Beyond Knightsbridge and Mayfair, most foreign investors either live in London or intend to rent their properties out, according to Jones Lang LaSalle: Hong Kong Chinese and Singaporeans usually buy London flats to provide a retirement income. Some are drawn to London by its universities—around 33% of newly built properties bought by foreigners are intended for student children to use, according to Knight Frank. Others value Britain’s light property-tax regime: council tax does not rise much with the price of homes. For Asian investors, the fall in the value of sterling since 2007 makes London housing seem cheap.

Foreign competition may well price some British people out of buying flats to live in. But British buy-to-let investors—who can often obtain cheaper mortgages than first-time buyers—are a bigger cause of falling home-ownership rates. Buy-to-let investors have been the “success story” of the London property market because they have developed a flourishing private rental sector, however, unless the supply of new properties into the market is maintained the buy-to-let investors can often “crowd out” the first time buyers.

Without foreign money, many flats might not have been built and the London construction industry would have suffered. Unlike British buyers, foreign buy-to-let landlords tend to prefer newly constructed properties: around 73% of new central London flats are sold abroad. Crucially, they are willing to buy flats “off-plan”, years before they are even put up, improving certainty and cash flow for developers.

When recession hit in 2008, bank finance to build new flats all but dried up, according to Savills. But in London, off-plan sales to foreigners helped to finance many projects, reducing the need to borrow scarce capital. In London, house building overall fell by just 20% between 2008 and 2012—and in some inner-London boroughs it increased. In Manchester, by contrast, where the population is growing just as quickly, the slowdown in construction was much more severe.

Asian investors tend to like blocks of high-rise flats with features such as communal gardens, roof terraces and underground car parks. They are careful and selective, sometimes insisting on American-style services such as concierges and laundry.

As the housing market recovers, British investors are increasingly copying foreigners: flats at Embassy Gardens in Nine Elms were mostly sold off-plan to natives this year. Meanwhile the foreign money may be spreading farther out and buying flats in places such as Manchester and Liverpool, where rental yields on city-centre flats can be extremely high.

We have to increase the supply of all tenures in London, in order to maintain our place as a global city and be the engine that drives the UK back to prosperity and part of that solution is an increase in funding of low cost homes at affordable rents.

Well written blog and very informative. Completely agree with you about the tenures.